Some say we humans are made at the moment of conception. But I don’t agree. That’s when our bodies begin to be made, yes. But our souls are knit together in tragic and heroic moments, sometimes years before we are born, when the messages of our families are formed in the crucible of human experience.

What follows is an important moment in the making of me. It happened in 1957 on a typical Saturday afternoon at a shoe store in Marshall, Texas.

My father was 20 years old in 1957 and a student at East Texas Baptist College in Marshall. He worked for Louis Kariel selling shoes at the Hub Shoe Store, a Marshall institution that was in business on the town square for over a hundred years.

You might remember that the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in 1954 in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case that declared school segregation to be unconstitutional. In 1957 the governor of Arkansas called in the National Guard of his state to block the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. President Eisenhower deployed Army troops and took control of the Arkansas National Guard, forcing the school to admit its first African American students.

I’m guessing you’ve seen the classic photos of that event.

So that was 1957.

Now Marshall is in deep East Texas. That part of our state was and is fiercely conservative. You would have had a hard time finding any white people in Marshall in 1957 who were happy about desegregation. So it was that on that fateful Saturday afternoon, the Hub Shoe Store was filled with customers and the conversation turned to recent events in Arkansas. The consensus among 100% of the store patrons was that the country was going to hell in a hand-basket, the blacks were taking over, and by God something needed to be done about it. Some suggested that the president ought to be impeached for his actions.

That’s when young Hollie Atkinson decided he needed to speak up.

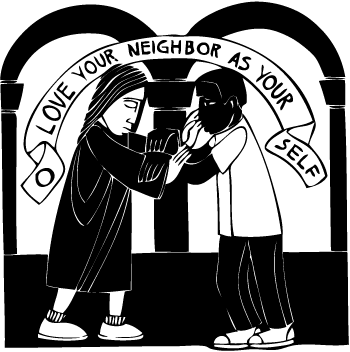

What you don’t know about my father is he had a religious conversion in high school followed by what can only be described as a mystical encounter with God in the football locker room of Livingston High School, also in East Texas and about two hours south of Marshall. When my father became a Christian, he did not understand Christianity to be one-and-the-same with conservative politics. That’s a more modern development that is a tragedy and a travesty. My father understood Christianity to mean that he would read the scriptures, learn about what Jesus taught, and live accordingly, regardless of what anyone else thought about him.

Some months after his conversion the football coach asked him to gather up all the used football shoes so they could be given to the black high school across town. That’s how they did it in those days. The white school got new equipment and the black school got their hand-me-downs. As my father gathered the used shoes and put them into boxes, he had an inspired thought.

This is not right. It’s not right that we should get new equipment and the kids across town should get the old stuff.

You might think the context of this revelation is a bit mundane and even silly. But if you consider the life of a high school boy in East Texas in the 1950s, the locker room filled with football equipment was a beautifully appropriate medium for a divine message. And if you consider that no white person in my father’s life would have articulated this truth for him or been anything but angry with him were he to speak about it, the whole thing becomes downright miraculous.

I’m convinced it was a message straight from God. Perhaps a message that had been delivered to others before my father but was ignored because it was too inconvenient a truth to be put into practice. I don’t know what it was about Hollie Atkinson that made him different, but he heard the Word of the Lord and never looked back.

I’m guessing that young Hollie didn’t say much about his new thoughts on racial harmony for a few years, as it settled into his way of thinking and being, where it grew and matured into a full-blown conviction that racism was a terrible evil in the world. Accordingly, on that Saturday in the Hub Shoe Store in Marshall Texas, he could not remain silent. And so he got the attention of those present and had his say. He announced to the people in the store that, in fact, the opposite of what they were saying was true.

“We should impeach the president if he does NOT take action in Arkansas. Because the Supreme Court of our land has said that segregation is unconstitutional. And as you know, our president is duty bound to uphold our constitution.”

I think you can imagine the scene that followed. There was yelling. My father was called a nigger-lover. People told the store owner that my father should be fired, and they weren’t going to be giving The Hub Shoe Store their business anymore if he worked there. The store emptied pretty quickly, leaving my father alone with his boss, Louis Kariel.

What you don’t know about Louis is that he was a devout Jewish man and a leader in the Jewish community of East Texas in the 50s. Just 12 years or so after the end of World War II, Mr. Kariel knew exactly what it meant to be a persecuted and hated minority. He and my father were bonded together in friendship over the event. My father was not fired and worked at the store the entire time he was in college. The Hub Shoe Store survived into the early 21st century. Angry bigoted people are often lazy people, and apparently the threats of taking their business elsewhere were soon forgotten.

My father remains friends with the Kariel family to this day and attended Louis’ funeral in the 90s in Marshall. Hollie fought battles over racism at churches he pastored in Texas throughout his career. He is retired now. He never told this story publicly, as far as I know. It’s not his style. Fighting racism was not his reason for being. It’s just that his idea of the gospel of Jesus had no place for racism. Racism never made sense to him.

I think he would have said it this way: he was too busy telling people about Jesus and trying to live right to have any time to worry about something as silly as the color of someone’s skin.

As for me, I heard the story when I asked my father to help me understand how he grew up in East Texas in the 40s and 50s and came through his childhood with such strong opinions on race relations. His telling of this story impacted me powerfully.

When I was in seminary I made a secret vow to God. I had an intuitive sense that at some point in my life, my sense of rightness and goodness and of what Jesus wanted me to do would be at odds with my community or perhaps with a church that employed me. When that day came, I prayed I would have the courage to say and do what I thought was right, whatever the cost.

Certainly seminary Gordon wanted very much to be counted as a good and faithful servant of Christ. But I had a more visceral and emotional motivation as well. For you see, I have always wanted to be worthy of being Hollie Atkinson’s son.