I grew up in a world where one did not miss church on Sundays. Ever. It just wasn’t done, at least not in my family. We were among the insiders of the church who never missed, gave generously, and basically ran the show. There were lesser-committed members who attended maybe half the time. They weren’t exactly looked down upon, not exactly, but they were encouraged in sermons and Bible studies to step up their game and be a little more committed to the church, which we equated to being committed to Jesus.

There was also the C&E crowd – Christmas and Easter – who showed up twice a year to perform some sort of holiday penance. They sat awkwardly in the pews and struggled to comprehend the nuances of our liturgy and worship practice. They were welcomed warmly and made to feel at home, but they were clearly outsiders and pretty much the same as the people who

Never

Went

To

Church

At

All.

The outsiders. Yes, we would see them through the windows of our car as my father drove us to church. Unshaven men in robes shuffling down their driveways to retrieve the Sunday paper, people in shorts and t-shirts buying gas, families loading up the car for a trip to the park, and people walking leisurely into diners for their Sunday breakfast.

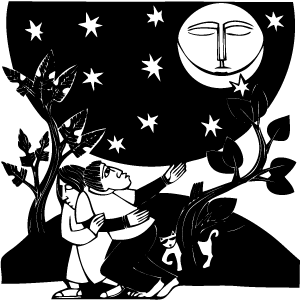

I was always fascinated by these people as a boy. Having no category for metaphysical considerations outside of my religious tradition, I assumed they never thought much about God or the meaning of life at all. They just did whatever they wanted to do on Sundays, which seemed like it was probably fun but was scary, like forbidden fruit.

By the time I got through college and seminary and became a pastor, I had come to some conclusions about the people who never go to church. It seemed to me that a single human lifetime was too short for a person to tackle questions of ultimate meaning on her own. You could spend your whole life cobbling together some sort of worldview, pulling bits and pieces from here and there into your own personal philosophy. We Christians begin with a starter pack, you might say. A set of beliefs and practices with two millennia of history behind it. With that robust starting point you can dedicate your life to polishing the details, working out the rituals, and even customizing a bit within some parameters.

That’s how I saw things then. You should go to church. It just made sense to me.

I left pastoral ministry in 2010, following an intuitive sense of calling away from what I knew so well. People would ask why I was leaving and I never knew quite what to say. It was just time to go. Without the urgency of preparing sermons every week I found myself meditating on a single passage of scripture. This one:

Matthew 7:21-23

Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord”, will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only one who does the will of my Father in heaven. On that day many will say to me, “Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many deeds of power in your name?” Then I will declare to them, “I never knew you; go away from me, you evildoers.”

I didn’t read the Bible for five years. Those three verses haunted me, so I thought only about them. I think it is clear that Jesus was speaking not to the outsiders of his religious world, but directly to the insiders. To the church people, you might say.

In time I found myself asking one question:

If we could magically transport Jesus from wherever Jesus currently resides (Seated at the right hand of the father for you orthodox, floating gently in the archetypal soup of Christian literature for you liberal believers, or simply brought back from the dead for you agnostics and skeptics) what would he say about the Christianity of our culture?

Would he embrace us warmly as children who faithfully carried on the traditions of his teachings?

Would he angrily denounce us for our materialism, our nationalism, the gnats we have strained and the camels we have swallowed, and the spendthrift way we have expended our resources to prop up a comforting institution?

Or – most distressing of all – would he not see in us any connection to him at all. Would he simply not recognize us?

I find the first of these to be unlikely, which is heartbreaking. The second and third options are distressing and have led me into a season of wandering in a wilderness of my own making.

Now I am the unshaven man in his pajamas on Sunday mornings, shuffling to the computer to read the news. I am the man loading his mountain bike on Sunday for a day in the park. I am the man going into the diner for a late breakfast while the church people pass by in their cars, their children’s faces pressed against the windows.

And to the man who looked at me last Sunday morning at Whataburger, as I sat in my jeans and t-shirt eating breakfast tacos, while he stood in line in his suit with his daughter and her leathered-covered Bible, I can only say this:

I know what you’re thinking.