Everything that night was out of the ordinary. I was passing through La Vernia, Texas with time to kill. I don’t usually drive through La Vernia, and it’s rare that I’m on the road unless I’m supposed to be somewhere at an appointed time. It felt good to be in a small town without being in a hurry to get someplace else.

I was hungry and decided to see what La Vernia had to offer. I wasn’t interested in franchises. I wanted something local. So I drove from one end of town to the other to see what my options were. There was a Mexican food place, an Italian restaurant, another Mexican food place, and two steak houses. One of the steak houses looked fancy and new. The other advertised barbecue and steaks and was in a white cinder block building that looked like it had been there for decades. Also the parking lot was full. It was called Witte’s and that’s where I went.

The sun was going down and there was a red neon light in the window flashing on and off that said, “Open.” I stood just inside the door and looked around, getting the feel of the place. Every man except me was wearing a hat or a cap. Fifty years ago they would have taken them off indoors, but that’s optional now and generally people leave their hats on. Most of the tables near the door were filled with people laughing, drinking beer from bottles, and smoking. The smell of cigarette smoke in a restaurant – something you never see in large cities now – made me feel like I had gone back in time. I almost sat near the front just to enjoy the ambiance, but the truth is I like a few whiffs of a cigarette and then I get sick of it. So I passed through the crowd to the back where there were families and no one was smoking.

The back of Witte’s looked like it was added later. The roof beams were supported by rough cedar posts, so rough that some still had branches on them. There was a large basket on my table filled with saltines and packets of butter. Maybe people snack on buttered saltines in La Vernia, but I left them alone.

My waitress was middle-aged and friendly. She had dark hair that was piled up high on her head. I asked her what was good.

“The barbeque is real good. People come here for that. And the chicken fried steak is good too. Lots uh people come here to get that. It’s a rib eye steak. Chicken fried rib eye. It’s real good.”

“What about just the steak? A rib eye steak?”

“It’s real good too. People like it.”

“Okay, I’ll have that then. With a baked potato and some green beans.”

“How you want that cooked?”

“Medium I guess.”

It wasn’t the best steak I ever had, but it wasn’t anywhere near the worst. It was so thin there was no way they could cook it medium. There was no pink in the middle. There seemed to be three sections to it with lines of fat dividing them. There was also fat all around the edges, so I had some trimming to do. But it was tender and flavorful.

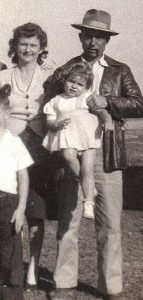

While I ate I looked around at the people. Most of the men were thick around the middle. Seventy years ago they would have looked like my grandfather. He worked for the Humble Oil company after a childhood in a sharecropper’s family. In photos from those years he stares solemnly at the camera from beneath the brim of his hat. He looks lean and hard and sunburned. He looks like a man who has not had an easy life and is not expecting it to get any easier. Food was expensive in those days, so working men often struggled to replace the calories they burned during the day. Papaw looked like he didn’t have an ounce of fat on him.

Things are different now. Some of these men sell insurance or work at the Walmart. But the biggest change is the cost of calories. Fatty foods and carbohydrates are cheap and plentiful. The men in Witte’s eat like their grandfathers, hoarding calories as protection against lean times. But there will be no lean times in La Vernia, because you can buy 5,000 calories at Walmart or the Dairy Queen for less money than a worker makes in an hour.

But of course, worrying about calories, your waistline, and your heart is for city boys. The crowd at Witte’s didn’t seem too concerned. And on that night neither was I. I heaped butter and cheese on my baked potato and relished every bite of my steak. When I finished, all that was left was the fat I had trimmed. And looking at it lying there on my plate, I realized I couldn’t remember what pure fat tastes like.

As a kid sometimes I’d take a bite of roast or brisket or, occasionally, a steak and be surprised to find it rubbery and soft and slick. A chunk of fat, burned dark, had slipped into my mouth incognito. But as we get older we learn fat’s camouflaging tricks. I’m 51 years old and don’t get fooled by fat anymore.

But from what I read, people in my grandfather’s generation were not so averse to eating fat. My grandfather’s favorite salad dressing was bacon grease. He would also spread hardened bacon grease on a sandwich instead of mayonnaise or mustard. When you’re struggling to consume enough calories to get you through the next work day, the fat is the most valuable part of the animal, since a gram of fat has more calories than a gram of protein.

So there I was, looking at the fat on my plate and listening to the laughter and the buzzing conversation of the good people of La Vernia. I started wondering what fat tastes like. Seventy-five years ago I assume I would have eaten it along with the meat and been glad to get it. But now I cut it off and shove it to the side of my plate as if it has no value.

I pushed a few pieces of fat around with my fork and poked at them.

And then I decided to eat some

Part two coming as soon as I figure out where this thing is going.